I wrote an earlier blog post (http://oldagesticks.blogspot.com/2013/06/crimes-against-humanity-lions-and.html) in which I accused Western countries, and especially the United States (sanctimonious self-appointed policeman of the world), of being hypocritically less concerned about the "kind" of crime committed by Syria (i.e., killing of civilians) than about the "degree" or "intensity" of the crime (i.e., egregious and systematic killing, rather than the more discreet, gentlemanly killing practiced by the world's "good guys.")

President Obama's recent remarks, however, have made it clear that the focus of my criticism was actually wrong. I was discussing the wrong kind of kind, i.e., the killing. Silly me. Apparently, neither the U.S. nor any other nation state has any but the most generically pious objection to the "degree" of killing going on in Syria--or indeed, to intramural killing itself (as a "kind" of criminal act).

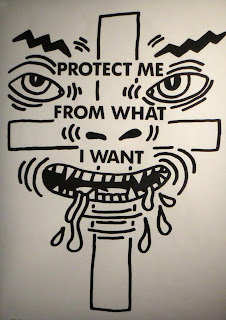

No, what the debate and the moral outrage is actually about is, well, the WEAPON supposedly used to accomplish the killing--in this instance, lethal gas. So yes, in a sense, we are discussing "kind" rather than "degree." But it isn't the kind of outcome that is condemned (except in platitudinous lamentations). Rather, it is the kind of means by which the civilian massacres were achieved. The United States, it turns out, can quite easily tolerate killing--a kind of result--but it cannot allow killing by gas--a kind of means to that result--to go unpunished.

So, killing--in some considerable degree--well, that must be accepted, as it always has been in omnia saecula saeculorum. But chemical weapons--this unholy kind of killing instrument is villainous, reprehensible, unacceptable and, yes, self-evidently immoral. Thou shalt not kill by lethal gas, for the United States will not hold him guiltless, that killeth by lethal gas.

So, killing--in some considerable degree--well, that must be accepted, as it always has been in omnia saecula saeculorum. But chemical weapons--this unholy kind of killing instrument is villainous, reprehensible, unacceptable and, yes, self-evidently immoral. Thou shalt not kill by lethal gas, for the United States will not hold him guiltless, that killeth by lethal gas.Napalm, I patriotically hasten to point out, is merely a chemical "agent," not a gas. And Agent Orange is a "defoliant."

Now, Syria, the reasoning goes, has broken the Lethal Gas Commandment (set forth in the 1927-29 Geneva Protocol which Syria ratified in 1968, though it never signed the Chemical Weapons Convention and therefore is technically not bound by it). In any event, morality is morality. A Commandment is a Commandment. God clearly does not want mankind to kill in this horrible way (and here I acknowledge--without sarcasm--that it truly is horrible). Other ways (knives, guns, missiles, cluster bombs) are, however, morally acceptable and, indeed, according to the NRA, some of these should probably be deployed to protect children in public schools in the United States). Then, too, buried somewhere within the legalistic Leviticus of U.N. documents, there is probably a document laying out the rules for "kosher" slaughter of human beings (the Protocol itself?).

And so, the United States, as the divinely (i.e. self-) appointed enforcer of kosher/halal killing, is now mustering its missile-girded hosts along the coastline of sinning Syria (the Philistines are gonna get it again). But, says Obama, we have no intention of intervening to stop the killing itself. We are merely going to punish the perpetrators for the kind of instrument used in the killing--the weapon that makes the killing treif. This is called, with medical detachment, a "surgical strike." I think, though, that religious terminology might be more appropriate. Because isn't the military operation we are contemplating an attempt to "purge" a country of both unclean, heretical practices and those who impiously engage in them? Aren't we really just insisting that the killing be done with proper utensils? So perhaps we could name the operation "Hallaf" in honor of the knife that is prescribed for ritual and thus "legitimate" slaughter. Or, if we wanted to stress the more Christian notion of purging the world of heretical practices, we could also call the strike "Operation Auto-da-Fé."

And so, the United States, as the divinely (i.e. self-) appointed enforcer of kosher/halal killing, is now mustering its missile-girded hosts along the coastline of sinning Syria (the Philistines are gonna get it again). But, says Obama, we have no intention of intervening to stop the killing itself. We are merely going to punish the perpetrators for the kind of instrument used in the killing--the weapon that makes the killing treif. This is called, with medical detachment, a "surgical strike." I think, though, that religious terminology might be more appropriate. Because isn't the military operation we are contemplating an attempt to "purge" a country of both unclean, heretical practices and those who impiously engage in them? Aren't we really just insisting that the killing be done with proper utensils? So perhaps we could name the operation "Hallaf" in honor of the knife that is prescribed for ritual and thus "legitimate" slaughter. Or, if we wanted to stress the more Christian notion of purging the world of heretical practices, we could also call the strike "Operation Auto-da-Fé."

_-one_leg_raised.jpg)